sAUDI aRABIA

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is located on the Arabian Peninsula, bordering Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Yemen, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea. 34.8 million people live in Saudi Arabia, predominantly Arab (90%) with an Afro-Asian minority (10%). The state is officially Muslim, with 85-90% of citizens practicing Sunni Islam and 10-15% practicing Shia Islam. About 30% of the population is an expatriate community practicing other religions including Eastern Orthodox, Protestant, Roman Catholic, Jewish, Hindu, Buddhist, and Sikh.

Good news! Raif Badawi is free!

Saudi blogger Raif Badawi was released from detention on March 11, 2022 after ten years in prison and 50 lashes in a public square simply for creating an online forum for public debate. Raif spent 11 extra days in detention past his original prison sentence, which ended on February 28. While this is a major victory for human rights, he has been given a ten-year travel ban. That means he will go a total of 20 years without seeing his family, who are now based in Canada. King Salman must lift his travel ban immediately.

urgent actions

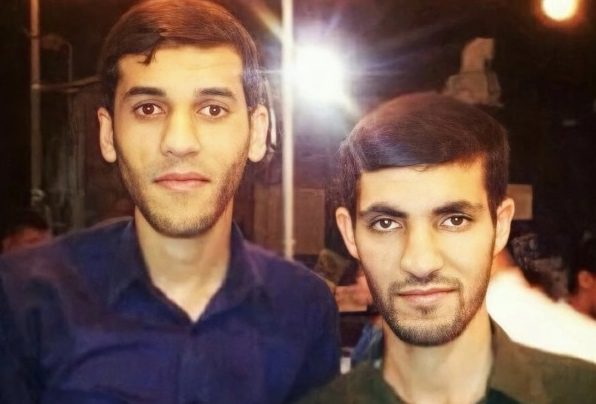

Halt Imminent Execution of Bahraini Men Sentenced after Flawed Trial

Saudi Arabia’s king must halt the imminent execution of Jaafar Sultan and Sadeq Thamer, two Bahraini Shi’a men who were sentenced to death on terrorism and protest-related charges following a grossly unfair trial in October 2021. Sultan and Thamer were arrested in 2015 and held incommunicado in solitary confinement for 3.5 months. They were only allowed to call their families 115 days later, but prison officials did not allow them to discuss the conditions of their detention. The Appeals Court upheld their sentences in April 2022. They could be executed in Saudi Arabia as soon as the King ratifies their sentence. Join Amnesty International’s Urgent Action to call on King Salman to halt these executions.

Saudi Arabia’s king must halt the imminent execution of Jaafar Sultan and Sadeq Thamer, two Bahraini Shi’a men who were sentenced to death on terrorism and protest-related charges following a grossly unfair trial in October 2021. Sultan and Thamer were arrested in 2015 and held incommunicado in solitary confinement for 3.5 months. They were only allowed to call their families 115 days later, but prison officials did not allow them to discuss the conditions of their detention. The Appeals Court upheld their sentences in April 2022. They could be executed in Saudi Arabia as soon as the King ratifies their sentence. Join Amnesty International’s Urgent Action to call on King Salman to halt these executions.

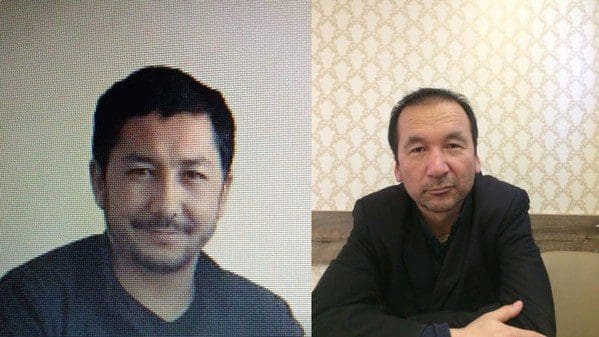

Stop Extradition of Uyghur Residents to China

Uyghur woman Buheliqiemu Abula and her 13-year-old daughter, her former husband Nuermaimaiti Ruze, and his friend Aimidoula Waili are at risk of forced repatriation to China following their arrests in March 2022 (Abula and her daughter) and November 2020 (Ruze and Waili). They are being held without any reason for their arrest or any charges presented to them. If sent back to China, it is highly likely they will face arbitrary detention, torture, and persecution. Click here to tell the Saudi authorities to immediately halt their extradition, which would amount to refoulement.

Mohammed and Hani al-Khudari

The health of Dr. Mohammed al-Khudari (84) continues to deteriorate while in detention. He is being deprived of adequate medical treatment for his advanced prostate cancer. His and his son, Dr. Hani al-

The health of Dr. Mohammed al-Khudari (84) continues to deteriorate while in detention. He is being deprived of adequate medical treatment for his advanced prostate cancer. His and his son, Dr. Hani al-

Khudari’s prison sentences ended on February 28, 2022, but they remain detained until the Supreme Court reviews the appealed sentences of all the defendants in the mass trial which both men are part of. Meanwhile, Dr. al-Khudari’s life is at serious risk in prison. Amnesty International urges the Saudi Arabian authorities to release both men immediately. Pending their release, they must be granted immediate access to adequate medical care. Click here to join Amnesty International’s calls on King Salman to release them both immediately and provide Dr. al-Khudari with urgent medical care.

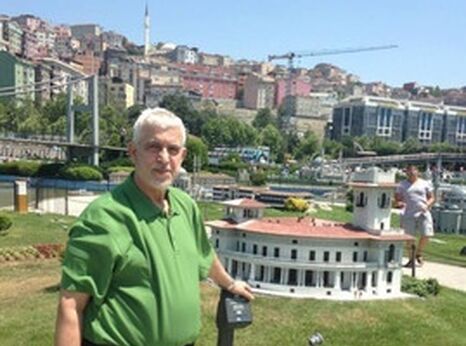

Abdulrahman al-Sadhan

On April 5, 2021, Abdulrahman al-Sadhan, a 37-year-old Red Crescent worker, was sentenced by the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh to 20 years in prison to be followed by a 20-year travel ban on charges relating to the peaceful exercise of his right to freedom of expression, and following a trial marred by violations, including possible torture used to extract a “confession.” He has been detained arbitrarily for four years, and is still being held without contact to his family and in solitary confinement. The Saudi authorities must grant Abdulrahman al-Sadhan’s immediate and unconditional release. Take action here

Ten Detained Egyptian Nubian Men

The Saudi Arabian authorities must immediately release and drop all charges against 10 Egyptian Nubian men who have been detained without charge for 16 months merely for trying to organize a remembrance event. Not only are these men being detained unlawfully, they have also been denied regular family contact and only allowed access to government-appointed lawyers, while at least two of them are elderly and in ill health. The Saudi Arabian authorities must ensure that they have full access to medical care, lawyers of their choice and regular contact with their families. They are due to are due to appear for trial on March 27. Click here to join Amnesty International’s calls to immediately and unconditionally release all prisoners of conscience detained solely for peacefully demanding reforms and exercising their right to freedom of assembly.

Executions in 2022

As of March 21, Saudi Arabia has executed 103 people in 2022. According to our logs since 2000, this is an unprecedented escalation in Saudi Arabia’s use of the death penalty. It’s the highest number of executions for a period of three months since 2000. On March 12, the Ministry of Interior announced the execution of 81 people, all of whom had been convicted of a wide range of offenses, including “terrorism”- related crimes, murder, armed robbery and arms smuggling. A number of those executed were also convicted of charges such as “disrupting the social fabric and national cohesion” and “participating in and inciting sit-ins and protests,” which describe acts that are protected by the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association. Read more here

Background

In 2020, repression of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly intensified. Among those harassed, arbitrarily detained, prosecuted and/or jailed were government critics, women’s rights activists, human rights defenders, relatives of activists, journalists, members of the Shi’a minority and online critics of government responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Virtually all known Saudi Arabian human rights defenders inside the country were detained or imprisoned at the end of the year. Grossly unfair trials continued before the Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) and other courts. Courts resorted extensively to the death penalty and people were executed for a wide range of crimes. Migrant workers were even more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation because of the pandemic, and thousands were arbitrarily detained in dire conditions, leading to an unknown number of deaths.

The country maintained economic and political sanctions against Qatar, along with Bahrain, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in the ongoing political crisis in the Gulf that began in 2017.

The Saudi Arabia-led coalition in the long-running armed conflict in Yemen continued to be implicated in war crimes and other serious violations of international law (see Yemen entry).

In March, the Saudi Press Agency announced that the Control and Anti-Corruption Authority (the Nazaha) had arrested 298 public sector officials and was investigating them for corruption.

In May, in response to plummeting oil prices and the economic impact of COVID-19, the authorities introduced austerity measures, tripling Value Added Tax to 15% and ending the cost of living allowance for state employees.

In November, the G20 summit was held virtually, chaired by Saudi Arabia. More than 220 civil society organizations pledged not to participate in the parallel civil society engagement process to protest against Saudi Arabia’s human rights record.

In July 2021, Amnesty International found that Saudi Arabian authorities have brazenly intensified the persecution of human rights defenders and dissidents and stepped up executions over the past six months, following a lull in prosecutions of activists and a sharp decline in use of the death penalty during Saudi Arabia’s G20 presidency last year.

In July 2021, the Pegasus Project, a ground-breaking collaboration by more than 80 journalists from 17 media organizations in 10 countries coordinated by Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based media non-profit, with the technical support of Amnesty International, conducted cutting- edge forensic tests on mobile phones to identify traces of NSO’s spyware. From the leaked data ad their investigations, Saudi Arabia was named one of 11 potential clients.

Arbitrary Detention and unfair trials

The authorities arbitrarily detained, prosecuted and imprisoned human rights defenders and family members of women’s rights activists for their peaceful activities and human rights work, including under the Counter-Terrorism Law and Anti-Cyber Crime Law. By the end of the year, virtually all Saudi Arabian human rights defenders were in detention without charge, or were on trial or serving prison terms.

Among those arbitrarily detained for prolonged periods without appearing before a judge or being charged was Mohammed al-Bajadi, a founding member of the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association (ACPRA), detained since May 2018.

In April, Abdullah al-Hamid, a prisoner of conscience and founding member of ACPRA, died in detention following medical neglect. He had written extensively on human rights and the independence of the judiciary.1 In late April, the authorities arrested writers and others for expressing sympathy over his death, including Abdulaziz al-Dakhil, an economist, writer and former Deputy Finance Minister.

More than two years after a wave of arrests targeted women human rights defenders and supporters, the authorities continued to detain incommunicado Loujain al-Hathloul and Nassima al-Sada for between two to four months at a time. In December, Loujain al-Hathloul was sentenced to five years and eight months in prison, after her case was transferred to the SCC in November. The court suspended two years and 10 months of the total prison term. Several other women activists continued to be detained and on trial before the Criminal Court in Riyadh for their human rights work or expression.

Unfair Trials

Grossly unfair trials continued before the SCC, a counter-terror court notorious for due process violations including mass trials.2 Among those who continued to be tried or were convicted after such trials were a woman human rights defender, religious clerics and activists charged with offences, including capital offences, arising from the peaceful expression of their views.

A mass trial of 68 Palestinian, Jordanian and Saudi Arabian nationals facing trumped-up charges under the Counter-Terrorism Law began in March before the SCC. Two of them, Mohammed al-Khudari and his son Hani al-Khudari, were charged with “joining a terrorist entity” understood to be the Hamas de facto authorities in Gaza. Both were forcibly disappeared during the first month of their detention and were detained incommunicado and in solitary confinement for two months. They had no access to legal representation from their arrest onwards.

In June, 14 individuals detained since April 2019 for their peaceful support of the women’s rights movement and women human rights defenders were charged under the Anti-Cyber Crime Law, the Counter-Terrorism Law or both. Among them was Salah al-Haidar, the son of Aziza al-Yousef, a woman human rights defender who remained on trial for her women’s rights work.

In September, eight people received final sentences for the murder of Saudi Arabian journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Turkey in 2018. The Criminal Court in Riyadh commuted five initial death sentences, and sentenced all eight to prison terms ranging from seven to 20 years. The authorities permitted the attendance of diplomats, but closed the trial to media and independent observers. Additionally, the identity of those on trial and the charges they faced were not disclosed.

Also in September, the SCC sentenced writer and academic Abdullah al-Maliki to seven years in prison for his tweets and other online posts in which he wrote about freedom of expression and political representation and defended ACPRA members. He was also accused of hosting an intellectual forum to discuss books and philosophy, on charges of “inciting public opinion against the country’s rulers.”

Death penalty

Courts continued to impose death sentences, and carried out scores of executions for a wide range of crimes.

In April, a royal order announced an end to the use of the death penalty against people aged under 18 at the time of the crime for offences that attract discretionary punishments under Shari’a (Islamic law). The order was aligned to the 2018 Law on Juveniles, which prevents judges from imposing discretionary death sentences on those aged under 15. This law does not prevent judges handing down death sentences for that age group in the case of hadd crimes (those with fixed and severe punishments under Shari’a) or crimes punishable by qisas (retaliation).

In August, in a long-overdue development, the Saudi Human Rights Commission announced that the country’s Public Prosecutor had ordered a review of the death sentences against Ali al-Nimr, Abdullah al-Zaher and Dawood al-Marhoun, who were at imminent risk of execution.3 The three young men had been arrested in 2012 when children and charged with offences relating to their participation in anti-government protests in the Eastern Province. In December, the public prosecution also reviewed its call for the execution of Mohammad al-Faraj, a member of the country’s Shi’a minority, who was arrested at the age of 15 for his “participation in [anti-government] protests” in the Eastern Province, and instead demanded a prison term.

The authorities failed to abide by international fair trial standards in capital cases, often holding summary proceedings in secret and without allowing defendants access to representation or legal assistance. Foreign nationals often did not have access to translation services throughout the various stages of detention and trial.

Freedoms of Assembly, association and Expression

The authorities escalated repression of the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly, including through a crackdown on online expression and undue restrictions on freedom of expression related to the government’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. They harassed, arbitrarily detained and prosecuted government critics, human rights defenders, family members of activists and many others.

In March, the Public Prosecution announced that social media posts that question, or instigate against, the COVID-19 curfew would be punished under Article 6 of the Anti-Cyber Crime Law, which carries penalties of up to five years’ imprisonment and a maximum fine of almost SAR3 million (US$800,000).

Courts frequently invoked the Anti-Cyber Crime Law to sentence government critics and human rights defenders for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, citing tweets or other peaceful online expression as evidence.

The authorities continued to ban the formation of political parties, trade unions and independent human rights groups, and to prosecute and imprison those who set up or participated in unlicensed human rights organizations. All gatherings, including peaceful demonstrations, remained prohibited under an order issued by the Ministry of Interior in 2011.

Members of the ruling family, former governmental officials and their relatives were among those arbitrarily arrested or detained. A year after her arrest, an official Twitter account confirmed in April the detention without charge of Basma bint Saud Al Saud, a daughter of former King Saud bin Abdulaziz Al Saud and a writer and human rights activist. Her family expressed concern about her health as she has underlying conditions that require medical treatment.

Rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTQIA+) people

“Homosexuality” remained prohibited in Saudi Arabia, punishable by flogging and imprisonment.

In July, Yemeni LGBTI rights defender Mohamed al-Bokari was sentenced to 10 months in prison followed by deportation to Yemen for charges related to violating public morality, promoting homosexuality online and imitating women. He was arrested after he appeared in a video defending the personal freedoms of LGBTI people.

Rights of Migrants

In March, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the authorities extended residency permits of foreign workers without charge, and the Saudi Human Rights Commission announced the release of 250 foreign detainees held for non-violent immigration and residency offences.

However, the approximately 10 million migrant workers in Saudi Arabia continued to be governed by the kafala (sponsorship) system, which gives employers disproportionate powers over them and prevents them from leaving the country or changing jobs without the permission of their employers, increasing their vulnerability to labour abuses and exploitation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this situation – alongside dire living conditions, scarce legal protection and limited access to preventive health care and treatment – put migrant workers in an even more vulnerable position and at higher risk from COVID-19.

From March onwards, thousands of Ethiopian migrants, including pregnant women and children, were arbitrarily detained in harsh conditions in at least five detention centres across the country. Detainees said that they lacked adequate food, water, health care, sanitation facilities and clothes. Cells were severely overcrowded and prisoners could not go outside. The specific needs of pregnant and lactating women were not addressed. Newborn babies, infants and teenagers were detained in the same dire conditions as adults.4

While it was difficult to establish the scale of deaths in detention and corroborate all such allegations, detainees interviewed said that they had seen seven bodies of inmates. Three women said they had had contact with a female detainee whose baby had died in detention. Eight detainees said they had experienced and witnessed beatings by guards and two reported that guards had administered electric shocks as punishment.

Torture and Other Ill-Treatment

Corporal Judicial Punishment

In April, the Minister of Justice issued a circular to all courts to implement the Supreme Court’s decision to end discretionary flogging punishments and replace them with prison sentences and/or fines. Flogging continued in cases where the punishment is mandatory under Shari’a.

It remained unknown whether the discretionary flogging punishment imposed on blogger Raif Badawi had been dropped. In 2014, he was sentenced to 1,000 lashes, 10 years in jail followed by a 10-year travel ban, and a large fine for “insulting Islam” and creating an online forum for debate. In January 2015, he received the first 50 lashes. Further floggings were delayed, initially on medical grounds and since then for unknown reasons.

Spyware Targeting

During the Pegasus Project investigation, evidence emerged that family members of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi were targeted with Pegasus software before and after his murder in Istanbul on October 2, 2018 by Saudi operatives, despite repeated denials from NSO Group.

His wife, Hanan Elatr was also repeatedly targeted with the spyware between September 2017 and April 2018 as well as his son, Abdullah, who was also selected as a target along with other family members in Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Women and girls’ rights

In July, members of the Shura Council, a body that advises the monarchy, proposed an amendment in the executive by-law to the Saudi Nationality Law to give permanent residency, without any fee or lengthy procedures, to the children of Saudi Arabian women married to foreign nationals. This was presented as an interim solution to shortcomings of the Nationality Law, which bars Saudi Arabian women married to foreign nationals from passing on their citizenship to their children.

In a positive development, also in July, a court ruled that “an adult, rational woman living independently is not a crime” in the case of Maryam al-Otaibi, a Saudi Arabian woman on trial in a case filed by her father – also her legal guardian – for leaving her family home. Maryam al-Otaibi had actively participated in the campaign to end the guardianship system. It remained unclear whether this signalled the authorities’ intention to end the criminalization of women fleeing their homes without the permission of their guardian, which allowed male guardians to initiate “absentees” cases against them.

Women and girls continued to face discrimination in law and practice in relation to marriage, divorce and inheritance, and remained inadequately protected from sexual and other forms of violence. Those who had experienced domestic abuse continued to need a male guardian’s permission to leave shelters.

Relevant Links

- 2020/21 Annual Global Report on Human Rights

- Formula 1 Grand Prix must not deflect attention from dismal human rights record

- Saudi Arabia: Authorities Ramp Up Repression After G20 Hiatus

- The Pegasus Project: Massive Data Leak Reveals Israeli NSO Group's Spyware To Target Activists, Journalists, and Political Leaders Globally

- MENA: COVID-19 amplified inequalities and was used to further ramp up repression

- Tell King Salman to Free Jailed Activists

- Saudi Arabia: Release Women Human Rights Defenders Immediately!

- Report: Muzzling Critical Voices

- 10 Facts About the Kingdom of Cruelty

Saudi Arabia Newsroom

May 23, 2022 • Report

Death Penalty 2021: State-Sanctioned Killings Rise as Executions Spike in Iran and Saudi Arabia

2021 saw a worrying rise in executions and death sentences as some of the world’s most prolific executioners returned to business as usual and courts were unshackled from Covid-19 restrictions, Amnesty International said today in its annual review of the death penalty.

April 13, 2022 • Press Release

Uyghur Child Among Four ‘Booked for Deportation’ from Saudi Arabia to China Tonight

Amnesty International has received credible information that Buheliqiemu Abula and her teenage daughter, 13, were made to take tests for Covid-19 today in preparations for their deportation to China. The police told them that they should be prepared to leave the deportation center at 9 pm local time today to board a flight bound for Guangzhou, China.

April 4, 2022 • Press Release

Uyghur Girl, 13, Among Four ‘Facing Deportation’ and Torture in China

Saudi authorities must immediately release four Uyghurs – including a 13-year-old girl and her mother – who are at grave risk of being taken to repressive internment camps if sent back to China, Amnesty International said today amid fears that deportation plans for the group may already be under way.

April 20, 2020 • Report

Death penalty 2019: Global executions fell by 5%, hitting a 10-year low

Saudi Arabia executed a record number of people in 2019, despite an overall decline in executions worldwide, Amnesty International said in its 2019 global review of the death penalty published …

February 26, 2019 • Report

Human rights in the Middle East and North Africa: A review of 2018

The international community’s chilling complacency towards wide-scale human rights violations in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has emboldened governments to commit appalling violations during 2018 by giving them …

December 9, 2018 • Report

Oppressive, sexist policies galvanize bold fight for women’s rights in 2018

Women activists around the world have been at the forefront of the battle for human rights in 2018, Amnesty International said today as it launched its review on the state …

February 18, 2016 • Report

Amnesty International State of the World 2015-2016

International protection of human rights is in danger of unravelling as short-term national self-interest and draconian security crackdowns have led to a wholesale assault on basic freedoms and rights, warned Amnesty International as it launched its annual assessment of human rights around the world. “Your rights are in jeopardy: they are being treated with utter contempt by many governments around the world,” said Salil Shetty, Secretary General of Amnesty International.

August 24, 2015 • Report

Amnesty International Report: Rampant Executions in Saudi Arabia Fuelled by Justice System ‘Riddled with Holes’

Hundreds of people have been condemned to death after being convicted in unfair trials under Saudi Arabia’s deeply flawed judicial system, said Amnesty International in a new briefing published today.

February 25, 2015 • Report

State of the World 2014/2015

This has been a devastating year for those seeking to stand up for human rights and for those caught up in the suffering of war zones. Governments pay lip service to the importance of protecting civilians. And yet the world's politicians have miserably failed to protect those in greatest need. Amnesty International believes that this can and must finally change.

May 23, 2013 • Report

Annual Report: Saudi Arabia 2013

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Head of state and government King Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz The authorities severely restricted freedoms of expression, association and assembly and clamped down on dissent. Government …